Averse to Adverbs

Another week, another chapter in Steering the Craft by Ursula K. Le Guin. This time it’s Chapter 5: Adjectives and Adverbs. If I thought any of the previous ones were short and sweet, they’ve got nothin’ on this one. Le Guin only needs four pages to say what she wants to say regarding this topic—and half of those pages are for the exercise and critiquing said exercise.

So! Down to business!

Here’s the best way to sum up her general idea on adjective and adverb usage: Be efficient and precise. Word economy is her focus.

She gives us imagery that paints prose almost like a body. Specifically, how a body has a fat vs. muscle ratio. If you use adjectives and adverbs too indulgently or in a lazy fashion, you’re condemning your prose to obesity. You gotta think of the quality of the adjective or adverb you’re using. What nourishment does it provide your story and wordsmithing?

Now, perhaps you’re thinking, I don’t use too many of those types of words when I write. So, let me make some inquiries:

Are you prone to using the qualifiers rather or a little?

Are you more likely to say they ran quickly as opposed to they raced?

Do you throw around too many kind of’s or sort of’s or just’s?

Do things suddenly happen in your stories? Or are they somehow happening?

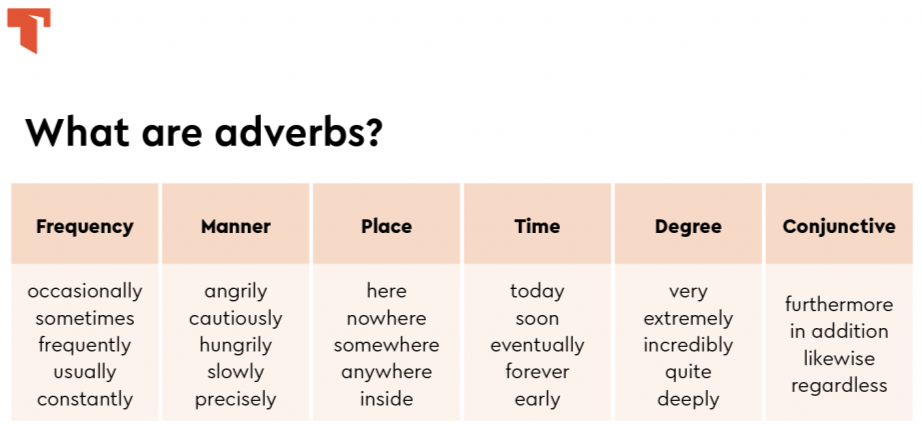

Let me also direct your attention to this infographic from Thesaurus.com because it could be the case that it’s been a while since you learned the formal definition of what an adverb is so you’ve forgotten that that word encompasses all these modifiers (and many more):

Our word habits are things Le Guin would have us alert to. Not because you can’t ever use adverbs and they’re signs of bad writers; rather, she wants us to not over-use them. They’re simple enough words and phrasing that you may not even notice just how much they populate your prose.

You must ask yourself: Are you feeding your story nourishing words and structure, or are you running it ragged with adjectives and adverbs you’ve already exhausted in the first chapter?

One thing Le Guin doesn’t point out but that I will now is that, while you should be mindful of your wordsmithing at every stage of the game, these considerations are more important for once you finish your first draft. It’s always better to write the dang story, even if the first iteration is messy with cringe-worthy scenes or underdeveloped character arcs. What do you think the editing process is for?

And, when you do get around to revision and parsing through your story line-by-line, take care to notice where you could use a fresh turn of phrase. Notice just how many times you use the same adverb as a point of transition in action. Notice the ways you qualify things and if you only really know one or two ways to do that.

Being able to identify those weak areas of your writing means knowing precisely where you need to grow. It gives you a measure of wisdom that you’ll take into the next draft or new story.

The advice Le Guin concludes this chapter with is that she “recommend[s] to all storytellers a watchful attitude and a thoughtful, careful choice of adjectives and adverbs, because the bakery shop of English is rich beyond belief, and narrative prose, particularly if it’s going a long distance, needs more muscle than fat” (45).

To put into practice being mindful and exacting of adverb usage, Le Guin has an exercise for us that she always suggested in every workshop she ever facilitated. It’s an exercise she invented for herself when she was in her teens, and, throughout the course of her writing life, she found it incredibly helpful for the ways “it enlightens, chastens, and invigorates” (46).

EXERCISE FIVE: CHASTITY

Instructions: Write a paragraph to a page (200-350 words) of descriptive narrative prose without adjectives or adverbs. No dialogue.

The point is to give a vivid description of a scene or an action using only verbs, nouns, pronouns, and articles.

Adverbs of time (then, next, later, etc.) may be necessary, but be sparing. Be chaste.

Something different about this exercise is that Le Guin doesn’t want you to set a time limit. This one will be trickier than any of the others so far, so take your time with it.

As always, if you’re interested in sharing it with anyone, you know you can always send it my way. Good luck with this one, friend, and happy writing!